Yolanda López often felt like an outsider. At UC San Diego in the early 1970s, where she studied art, her focus on Mexican American subjects was dismissed by peers and professors. Political activism by Chicanos tended to exclude women. The mural movement by Chicano painters was dominated by men.

Frustrated, López began jogging around San Diego for the freedom and self-empowerment. (Also, for the practicality — she didn’t own a car.)

Even on the university track team, she was on the sidelines. In a photo of the team hitting the streets, the men — they’re all men — are on the asphalt. López is on the dirt shoulder.

Women’s marginalization has rarely been depicted quite so literally.

In a half-century of art making, López exhibited in group shows at galleries. But she was never the subject of a solo museum show during her lifetime.

One was in development in 2019. COVID delayed the show by a year.

“She passed away three months before it opened in her hometown of San Francisco,” says her son, Rio Yañez. López died Sept. 3, 2021 of liver cancer at age 78.

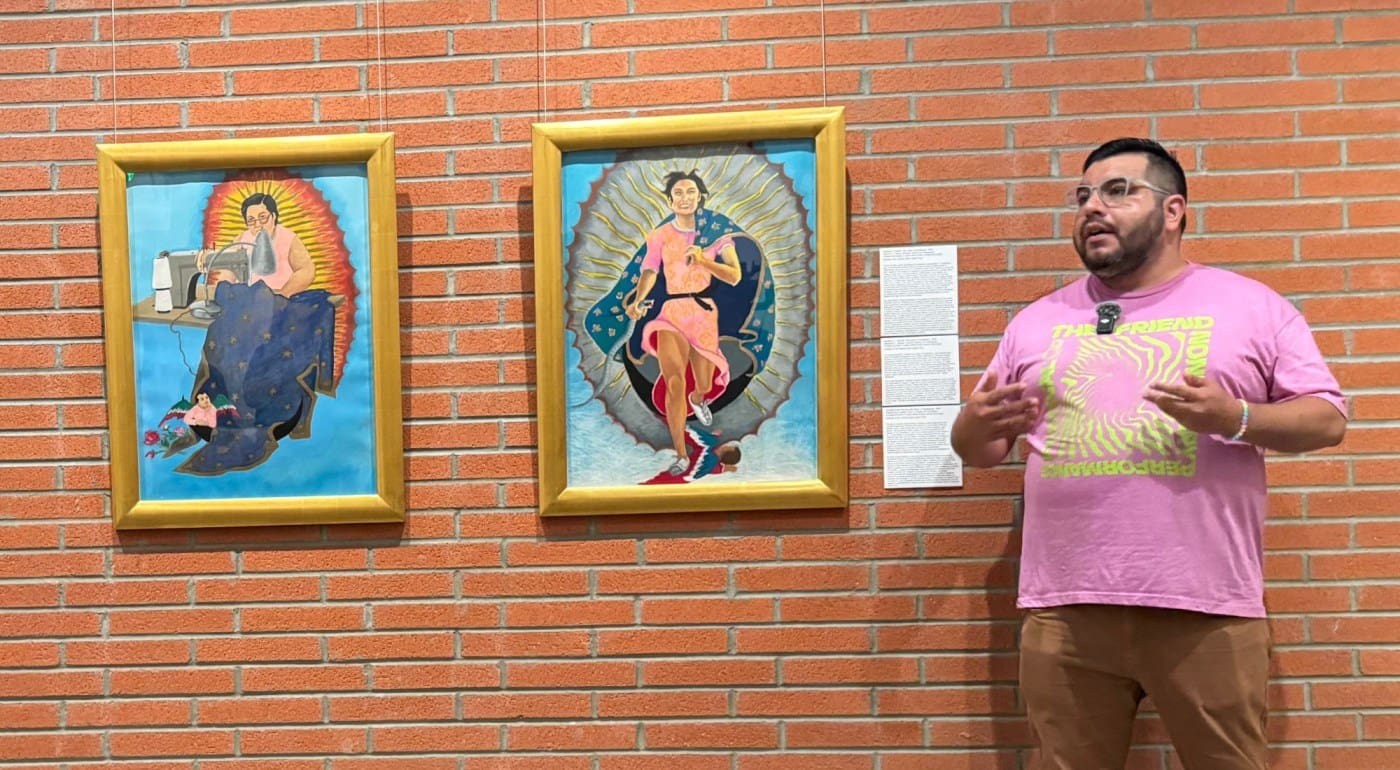

At Riverside’s Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture, López’s work now occupies the entirety of the second floor in two concurrent exhibitions.

“Portrait of the Artist” has works from the 1970s and ’80s. The show has been seen in San Diego, San Jose and Fresno before arriving in Riverside.

“A Woman’s Work is Never Done,” meanwhile, is a reconfigured version of that SF show. It encompasses López’s art from the 1960s to the 2010s, with works subsequently discovered — more on that shortly — and with more room to breathe.

The two shows feature paintings, political posters, photography, Xerox photocopy experiments, final projects, notebooks and studies made in preparation for some of her iconic works.

“It’s the most complete picture of my mom’s work that has ever been collected,” Yañez tells me in an interview in the galleries while visiting from Oakland. He curated “A Woman’s Work” with Angelica Rodriguez, López’s archivist.

Because the artistic director of the museum, María Esther Fernández, had been friends with his mother for two decades, Yañez says, “it was a really perfect fit for my mom’s work to be at The Cheech.”

For her part, Fernández says López was a mentor and friend who taught her how to think critically about art, imagery and museums. “When I went to San Francisco to see Yolanda’s show, I said, ‘We have to have it’” at the Cheech,” she tells me.

The twin shows, which opened Aug. 31, are in place through Jan. 26.

López’s most celebrated work is titled “Portrait of the Artist as the Virgin of Guadalupe.”

The Virgin is a frequent motif, as are López’s mother and grandmother. Her mother, Martha, was a seamstress for the U.S. Navy; her grandmother, Victoria, was a hotel maid.

In a 1978 triptych using the Virgin iconography, Victoria is seen in her maid’s uniform, Martha at her sewing machine, and López herself in running togs, hair in a ponytail, running toward the viewer exultantly.

Rodriguez says López was among the first artists to reappropriate the Virgen of Guadalupe for her own purposes. A few factors were at play.

López liked larger-than-life paintings by European masters but wanted to replace frilly English lords with working-class Chicanas. That subverted art conventions while also elevating women, whose invisible labor López saw as unappreciated.

“She wanted to see people like herself and her family in monumental form on museum walls,” Yañez says.

She also had a love of mythic women’s figures. A photo in “Women’s Work” shows López intently reading a 1970s “Wonder Woman” comic book. And she saw her own mother and grandmother, and perhaps herself, in the same heroic mold.

“She very much understood the symbolism and iconography without necessarily very much being a Catholic,” Yañez says. “It’s about showing the women in her family as sacred beings.”

Those and other paintings were controversial into the 1980s.

“I have vivid memories of being 4 and 5 years old,” says Yañez, 44, “and being in my mother’s kitchen when the phone would ring, my mom would pick it up, and it would be someone threatening to kill her.”

Several terrific 1970s self-portraits show López in her running gear, blazing along San Diego landscapes or past the UC San Diego campus, rendered smaller than her foregrounded figure. That was another example of her seeking to occupy space and reclaim power.

Rodriguez and Yañez are still sorting through López’s possessions three years after her death in San Francisco, her home for most of her adult life.

They have found art in old notepads, tucked inside the pages of books, in a file of old phone bills or in tax folders. With no means for archival storage, she had improvised. One painting was wrapped in an old shower curtain for protection.

López supported herself and her son not only by teaching art but through side hustles like wrapping gifts at Macy’s, selling Mary Kay cosmetics and working for the Census Bureau.

Very little of her work was ever sold.

“The sad truth is that she recognized in the 1970s and ’80s that she was never going to get her due,” Yañez says. “She retained all of it in her tiny one-bedroom apartment. The result,” he concludes, “is that we could have this show.”

brIEfly

In an essay about the pleasures in her neighborhood of autumn and Dodger fandom, novelist Susan Straight mentions an encounter with her letter carrier in Riverside. Straight writes: “He lives in San Jacinto and has driven to San Diego to pick up his girlfriend before driving to Dodger Stadium for a game; afterward it’s back to San Diego, then San Jacinto, nearly 300 miles in all.” As a letter carrier, he doubles as a road warrior.

David Allen, a U.S. male, writes Sunday, Wednesday and Friday. Email dallen@scng.com, phone 909-483-9339, like davidallencolumnist on Facebook and follow @davidallen909 on X.