RIVERSIDE — When Thomas Fuller returns to the campus of the California School for the Deaf, Riverside on Thursday, he should get a hero’s welcome. A silent one, delivered in American Sign Language, but no less heartfelt.

Fuller will be there to deliver copies of his book to the football team and staff, and he will have a book signing and question/answer session on campus in the evening. “The Boys of Riverside: A Deaf Football Team and a Quest for Glory,” released earlier this month, explores the process that enabled CSDR’s football program to go from doormats to dominance.

It is quite the story: A program with few winning seasons to show for most of its history in 11-man football is currently as close as it gets to a prep dynasty on the 8-man level: Three consecutive CIF Southern Section championship game appearances, back-to-back championships and a No. 1 Calpreps.com state ranking (and No. 19 nationally) in 2022.

And it’s how they’ve gotten there that is so intriguing. A group of deaf kids and deaf coaches are united in belief, steeled by adversity, and fueled by toughness and the idea that as long as they have each other, that’s all that matters. And, as Fuller’s book discusses, these players have advantages that hearing kids don’t.

Consider, for example, the silent count. We think of it, sometimes agonizingly so, when we watch a visiting offense trying to function in a packed, noisy stadium, frazzled by fan noise and often unable to stay onside. (For example, Matthew Stafford and the Rams in Detroit’s Ford Field in January, facing noise levels that reached 119 decibels – and, not incidentally, unable to function in the red zone in a 24-23 playoff loss.)

Not only don’t deaf football teams have to worry about communicating silently, they do it so well they just do not jump offside, on either side of the ball.

In the book, Fuller recounted the anecdote of current CSDR head coach Keith Adams as a deaf player on a hearing team at Lincoln High School in Stockton.

“He’s playing defensive end, and he never jumps offside,” Fuller recalled in a phone conversation. “His coach, who’s still around, told me, ‘I would tell my boys a decade after that I had a guy who never once jumped offside.’

“And then I talked to a teammate, who’s now a lawyer, and I said, ‘Hey, so, Keith never jumped offside once.’ And he was like, ‘We-e-e-l-l, there was a time when he got called offside.’ And I said I didn’t hear about that. He said, ‘Yeah. But then we looked at the tape. And he wasn’t offside. He just moved so fast that the refs thought he had moved offside.’”

The point, as Adams was quoted in the book communicating to his team: “There is no woe is me. Going out there in the real world, life is tough. We are going to have a little more adversity, But those are the cards that we were dealt. And you just have to work harder.”

Or, as he would say more pointedly: “You’re deaf. There’s no excuses. Just watch the ball.”

Focusing on what you can do, and refusing to worry about what you can’t, can be a superpower in itself. And it is true that not having one of the five senses can sharpen others. For example, research has shown that peripheral vision is enhanced in the congenitally deaf.

But not only are these kids great athletes playing a form of the sport that highlights their skills and toughness, with so much more open space than the 11-man game, but there’s “something about having all deaf players but also an all deaf coaching staff,” Fuller noted. “No offense to Pete Lanzi (the late coach who led CSDR from 1961 through 1985 and is, in many respects, the godfather of the program), but having your coaches and your players being all deaf, I think that puts you even one notch higher in terms of communication, in terms of being able to leverage deafness.”

CSDR’s football history, which dates to 1956, wasn’t a total zero but the highlights were few. The Cubs had five winning seasons between 1965 and ’70, reached the CIF playoffs six times from 1988 through 2009 and won league championships in 2004 and ’05 on the 11-man level, but never got past the first round of the playoffs before switching to 8-man in 2018.

“When I arrived here, almost every player said, ‘Oh, no, we’re going to lose,’ or, ‘Why do we have to practice so hard? Why do we have to be on time? Why do we have to lift weights,’” then-coach Len Gonzales said in a 2004 interview, through a sign language interpreter, after the Cubs clinched a league title. ” … A lot of our kids have no communication in their own homes. They’re very sheltered. Then they come here and they have the opportunity to open up and learn a lot. They realize they can do a lot of the things the same as (hearing) people can, except they can’t hear.”

Adams, incidentally, was an assistant on Gonzales’ staff.

The genesis for Fuller’s book was the memorable 2021 season, when CSDR was 12-0 going into the 8-man Division 2 championship game against Faith Baptist of Canoga Park. A West Coast correspondent for the New York Times based in San Francisco, Fuller learned of what looked like an intriguing story and came down to Riverside for a second-round playoff game.

CSDR ultimately lost the championship game to Faith Baptist 74-22 at Riverside’s North High, but their journey won them attention nationwide – including a spot on the field for the coin flip at the Super Bowl in SoFi Stadium, plus an appearance on the Kelly Clarkson Show, as well as that New York Times story.

And after writing that piece, Fuller decided this was too good a storyline to let go. He convinced his editors to let him have time off – “seven months,” he said – to embed himself with the team for the 2022 season for the book.

“They were like, ‘Well, who is going to cover the wildfires?’” he said. But they said yes.

And along the way – en route to a 12-0 2022 season and the first of consecutive championship game victories over Faith Baptist, this one 80-26 – Fuller not only attached himself to the football team but became attached to its city. There’s a good reason Riverside is part of the book’s title.

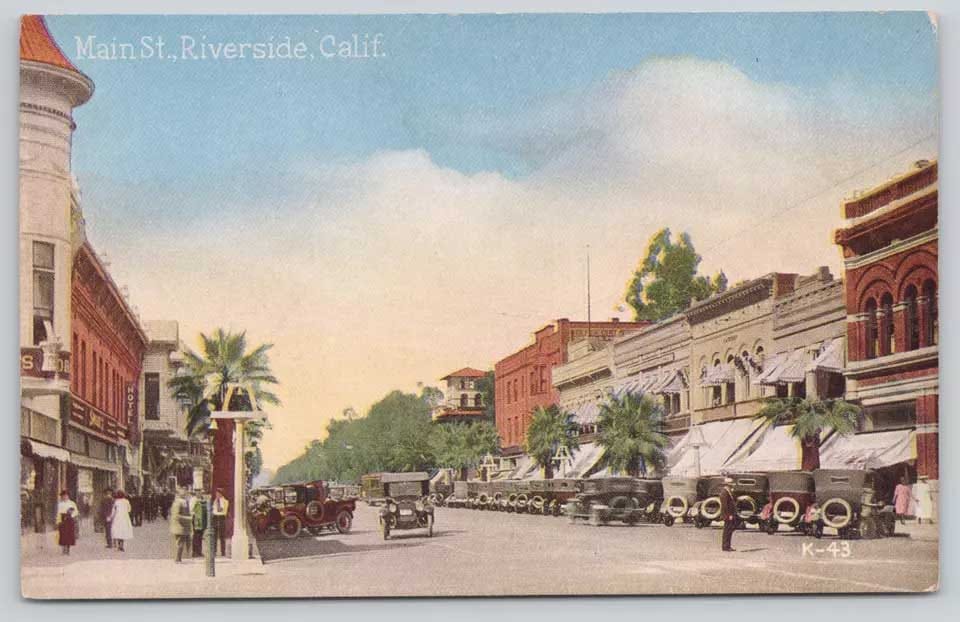

“I really enjoyed the fact that this was happening in Riverside, because to me, the Inland Empire is an underdog,” he said. “It’s not just the team that was an underdog. The Inland Empire does not get the respect that I think it deserves. People in L.A. don’t know that much about Riverside typically. People in Orange County might not know that much about Riverside. … So I thought that it was perfectly fitting that this team came from a part of Southern California that is often looked down on.

Related Articles

IE Varsity’s previews of the top high school football games Thursday, Aug. 22

Inland football preview: Centennial tops IE Varsity’s 2024 preseason rankings

Inland football preview: Centennial’s Husan Longstreet earns spot among nation’s top QBs

Author of book on California School for the Deaf, Riverside, football team to appear

Ron Main, Norte Vista coach and athletic director, remembered for professionalism and loyalty

“And I loved living in Riverside. I mean, when the book was over, I was getting used to my favorite local restaurants, getting used to walking through downtown Riverside, getting an omelet at my favorite breakfast place. I was getting used to walking up Mount Rubidoux every afternoon after writing or after practices.

“I think it’s fitting that what I think is the great American underdog story happens in an underdog town as well.”

If Riverside’s mayor, Patricia Lock Dawson, and the city’s Chamber of Commerce haven’t already been in touch, I’m guessing they will be soon.

jalexander@scng.com