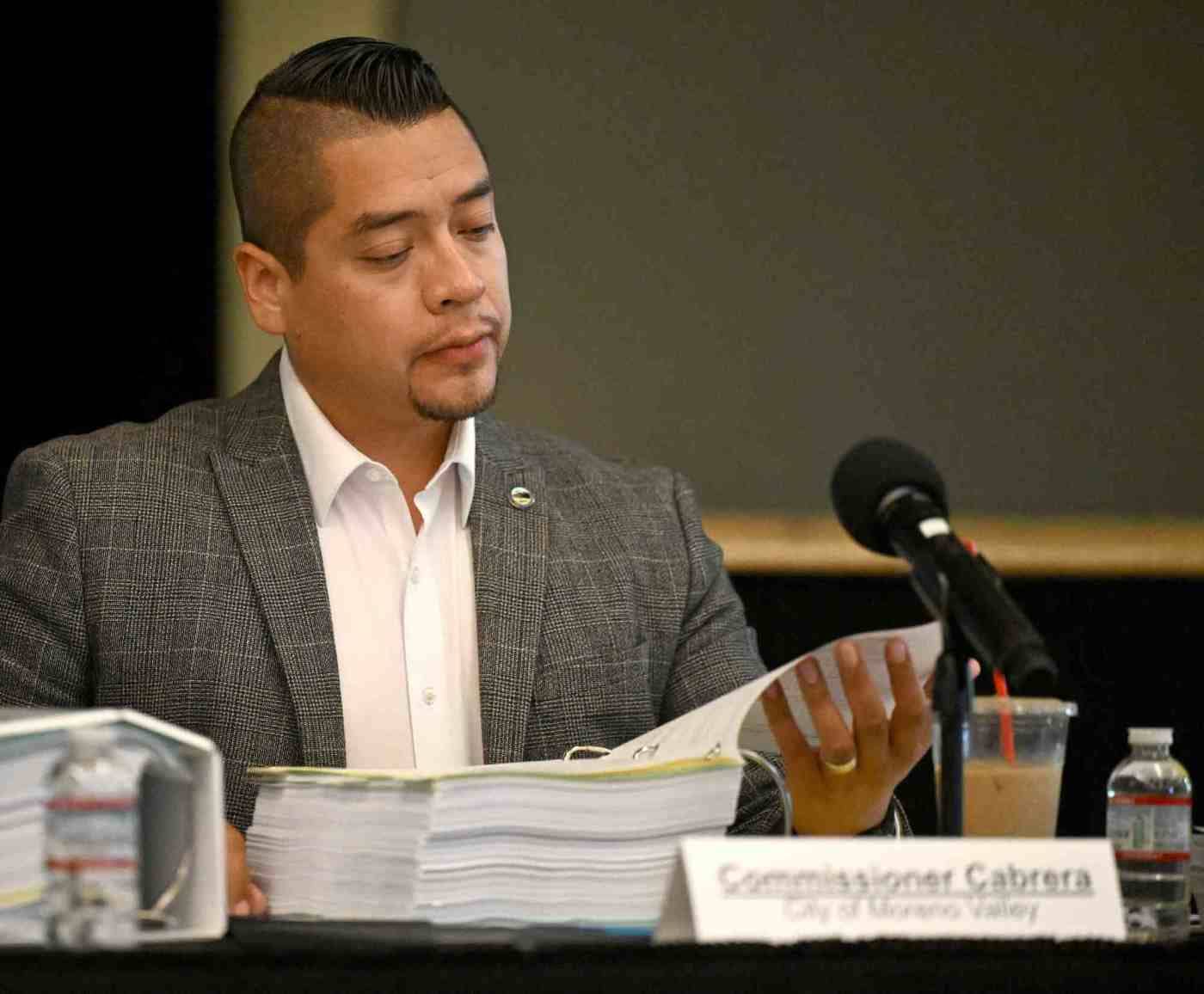

Moreno Valley’s mayor is suing his former employer, alleging he was retaliated against and later fired after refusing to use his public office to advance the company’s interests.

Ulises Cabrera also accused his supervisor of unwanted physical contact while working for Flock between February and June of last year. He filed his lawsuit in Riverside Superior Court in November, court records show.

Flock spokesperson Holly Beilin said via email that the company “takes these allegations seriously, and categorically denies each and every allegation as false.”

Asked to comment, Cabrera deferred to his attorney, Joseph Gross, who said via email that they could not discuss the case.

Headquartered in Atlanta, Flock makes surveillance cameras, license plate readers and other crime-fighting technology for public and private sector clients. In July 2023, Moreno Valley entered into a 5-year, $2.86 million contract with Flock to provide surveillance cameras and license plate readers throughout the city, according to a contract provided by city officials.

The city’s use of the cameras dates to 2021, when the Riverside County Sheriff’s Department, which provides police services for Moreno Valley, sought to standardize their use countywide to help deputies find stolen vehicles quickly, said Steve Hargis, Moreno Valley’s strategic initiatives manager.

“The use of Flock Safety cameras has been successful in locating stolen vehicles in the City of Moreno Valley, as well as assisting in other criminal incidents,” said Hargis, who added the camera program “effectively assists with solving several types of crimes efficiently and cost-effectively, which reduces the budget needs of the City of Moreno Valley.”

According to the lawsuit, Flock hired Cabrera, who was first elected mayor in 2022, as a community engagement manager who worked remotely and reported to a supervisor named Hector, who last name is not known, the suit states.

Two weeks into his new job, “Hector requested that (Cabrera) use his position as Mayor of Moreno Valley to benefit the company,” the lawsuit alleges, without specifying what Cabrera was asked to do.

“Concerned about the ethical and legal implications of this request, (Cabrera) promptly reported these concerns to Defendant’s legal counsel via email, copying Hector,” the lawsuit states, alleging that Hector “began exhibiting retaliatory behavior immediately thereafter.”

Hector made “passive-aggressive comments in Slack messages and emails” and “exercised unreasonable control over (Cabrera’s) work conditions,” including criticizing him “for working from a café instead of his home, despite Plaintiff’s position being designated as fully remote,” the lawsuit alleges.

During an April conference in Colorado, “Hector subjected (Cabrera) to inappropriate physical contact by repeatedly rubbing his leg against (Cabrera’s) leg,” the lawsuit alleges.

“Despite (Cabrera’s) attempts to move away, Hector persisted in this unwanted physical contact.”

In May, while working on a project in Carmel-by-the-Sea in Monterey County, Cabrera “discovered significant discrepancies in camera installation numbers,” the lawsuit alleges.

“(Cabrera) raised concerns about this misinformation, particularly as the same inaccurate data had been provided to both (Cabrera) and (Carmel-by-the-Sea’s) chief of police.”

On June 17, Cabrera told Hector about his wife’s pregnancy and his upcoming need for paternal leave, according to the lawsuit. Half an hour later, Cabrera was fired via Zoom, the lawsuit alleges.